Turquoise

Energy Ltd. News #30

Victoria BC

Copyright 2010 Craig Carmichael - August 3rd 2010

http://www.TurquoiseEnergy.com

Contents/Highlights:

July in Brief

(summary)

* Torque Converter - "type 5: clock escapement"

* Battery tab spot welder

* Working Ni-Mn

chemistry!

Battery chemie promises highest energy

densities,

"green", indefinite life, maintenance free, low cost.

Chevy Volt: I'm suspicious

* Delays, luxury car price, no TV ads... and specs

show abysmal

efficiency: HALF the miles/KWH of the EV-1.

* "Who Killed the Electric Car" is to be repeated with MiEV.

* It's all part of a century old pattern.

* Epilogue: A "typical example" of electric car suppression?

Mechanical or Magnetic Torque

Converter

Project

* "Crown" of

twisted sprockets

* Escapement "anchors"

* Principle seems to work

* Punch for making improved twisted sprockets; then a new one

for bigger ones.

Simple Capacitive Discharge/Resistance Spot

Welder Project

* Battery electrodes use spot welding for secure connections

* Electrodes: heavy Cu wires sanded to cone-shaped ends

* Trial 1: 10,000uF charged to 15 volts makes feeble welds on

thin battery jumpers

* Trial 2: 112,800uF @ 15 volts makes a bigger spark

* With short, heavy leed wires it zaps holes, pits

* With practice & technique, welds thin

battery tabs to battery.

* Shortest project yet, under 4 hours!

* Improved Model July 22nd

Turquoise

Battery Project

* Short Summary

* New Nickel-Manganese Battery

Chemistry Works! - for the first time ever, 2 volt alkaline

cells!

* Higher EV/PHEV battery energy densities are now possible, eg

140 WH/Kg and up!

* Made: Large 3" x 6" flat plate Ni-Mn Battery

* Depressing press news: bolt-down electrode

compactor is stronger than 12 ton hydraulic press

* Too much pressure; lots of bubbling: changed from

sealed dry cells to flooded, vented cells

* It's alkaline, even with salt electrolyte. pH read

12-13.

* Copper structural materials don't work in the positrodes -

rapidly corrode away. Trying nickel-brass plates.

* Copper negatrodes seem great!

* VERY gradually starting to hold charge - the voltages are

going up and lasting longer as the weeks pass.

* Stacking electrodes for higher voltage cells: ...dip in paint

or wax or something to seal edges?

* New, more powerful electrode compactor; bigger electrodes?

* Side thought: why are there no high energy density nickel-iron

batteries, eg, 70-80 WH/Kg?

* Exciting new Ni-Fe research - from India - is also applicable

to Ni-Mn. (next two items)

* Better electrode binder?

* Catalytic H2 + O2 => H2O gas recombiner reduces gas

pressures: allows maintenance-free sealed cells after all!

Newsletters Index/Highlights:

http://www.TurquoiseEnergy.com/TENewslettersIndex.html

Construction Manuals for making your own:

* Electric Hubcap Motor

(latest rev. 2010/02/xx)

- the only 5+ HP motor that can easily be made at home?

* Turquoise Motor Controller (latest rev.

2010/05/31)

- for the Electric Hubcap. (Probably there are commercial

controllers that would work, too.)

* 36 Volt Electric

Fan-Heater

- if you're running your car on electricity, you'll want a

way to defog the windshield and keep warm.

* Lead-acid battery longevity treatment - "worn

out" battery renewal procedure.

* Simple Spot Welder for battery tabs, connections (in This newsletter)

all at: http://www.TurquoiseEnergy.com/

July

in Brief

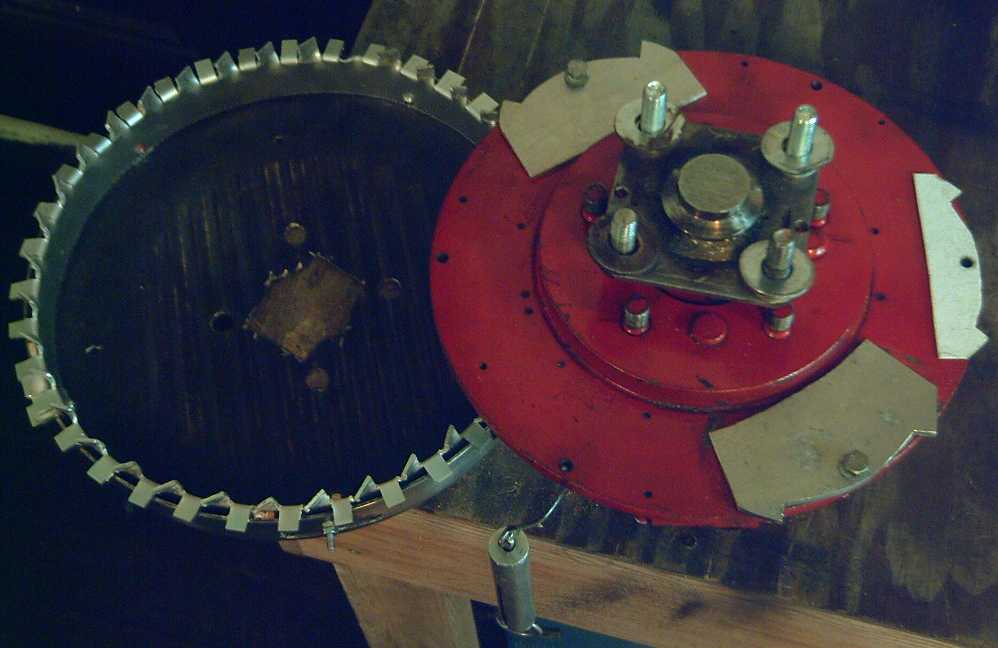

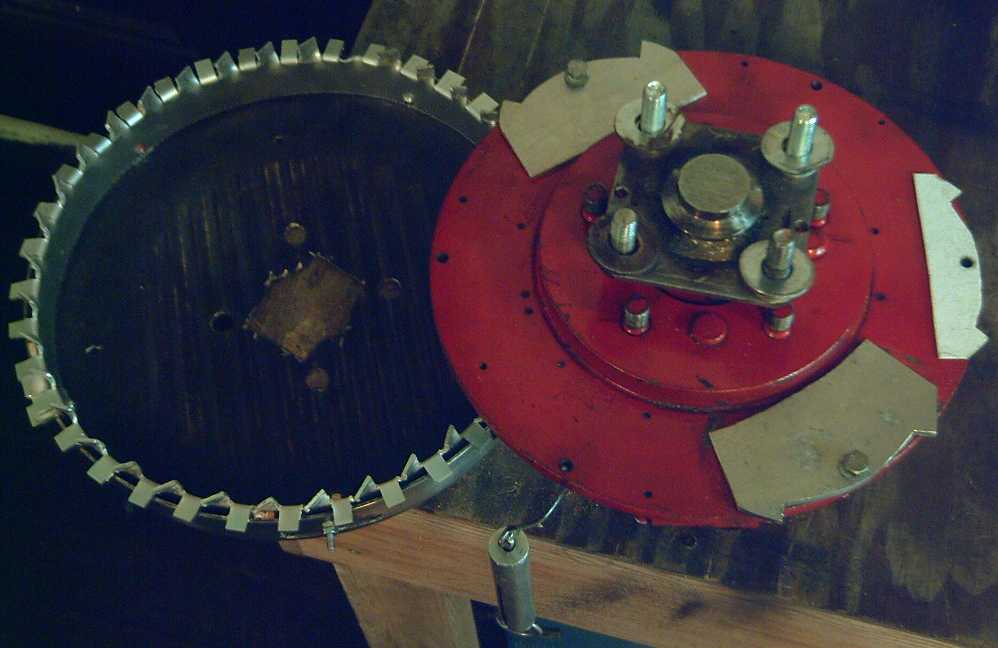

Latest Torque Converter:

Latest Torque Converter:

- Motor rotor/axle with escapements (top),

- converter drum (bottom),

- Nylon escapement bushings "pipe" (inset)

As I finally had the basic design details in my head,

everything looked good for trying out an 'escapement' torque converter

idea. A trial strip of aluminum with sprocket teeth was made.

Three escapement

anchors were made, a plastic 'template' and then two 'real' ones of

aluminum, and each one's shape was better refined. When I started, I

had only a meager

idea of what a 'right' or 'wrong' shape might be. I drilled and tapped

6

holes around the rim of the motor rotor for their pivot axles.

A hand turning test showed it seemed to do what it was

supposed to.

At low speed, the motor rotor and the converter drum turned freely

against each other, but by around just 30 RPM, the escapements buzzed

back

and forth, rather noisily, and the force on the stationary rotor was up

to around 2

foot-pounds, with two of six anchors installed.

Some time was lavished on making a punch

and die to stamp out 25 larger sprocket teeth around the rim of a new

sprocket strip. And I realized the drum could be made with from the

strip and a circle of flat aluminum plate, instead of finding a frying

pan

of exactly the right size and shape. This would be helpful to all

future builders, assuming the design worked. Then I finally set to

figuring out the best size and shape for the escapements and making

them.

After several hours of grinding, sanding, filing and

burnishing I got three that didn't jam and tried it out. Performance

was dismal! Heavier and more pieces, within reason, wouldn't be enough

to get it to move

the car.

Another vague plan is forming in my head, this one for

using the same sprocket gear and similar arrangement, but driving

the

escapements back and forth, which would directly turn the gear and

wheel, rather than relying on oscillating masses.

Capacitive Discharge Resistance Spot Welder

Capacitive Discharge Resistance Spot Welder

On the 15th I phoned around for a spot welder for battery

plates and leeds. There seemed to be none for sale in town.

For some comic relief I decided to see what

went into one. A little

investigation on the internet disclosed it's done in essence by

suddenly discharging capacitors, using a foot switch to trigger the

discharge. Electrodes were just heavy copper wire. Dispensing with all

formalities, I ended up being able

to weld thin battery tabs with a small power adapter feeding 0.11

farads - two dozen 4700uF, 25 volt capacitors

from

Queale Electronics (their largest size), which I later upped to 32:

0.15 F. These went via fat wires straight to the electrodes, which

arced as soon as the contacts were made. I found out other welders use

from 1 to 4.5 farads, but these operate through an SCR switch that

limits the current. Without the switch my 'underpowered' unit seemed to

be 'good enough'.

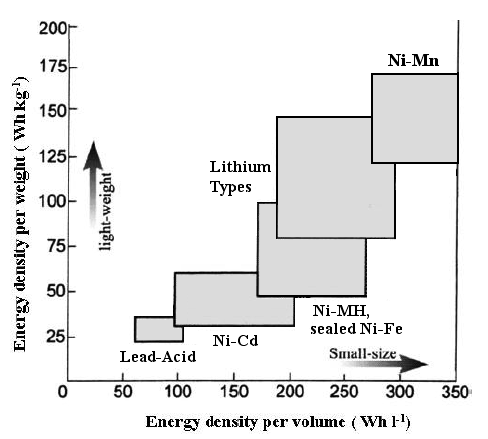

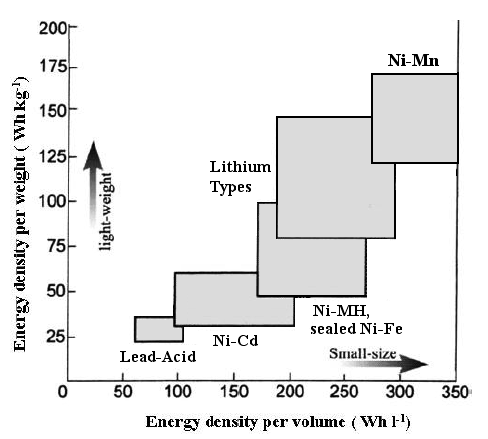

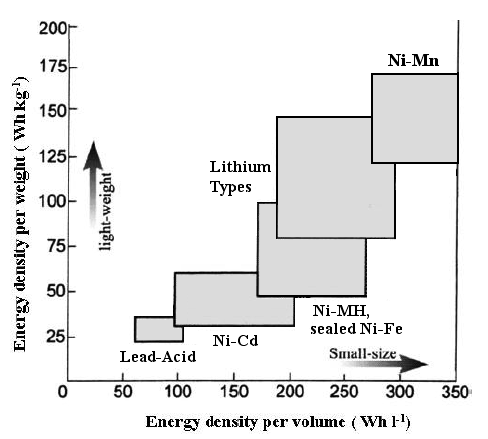

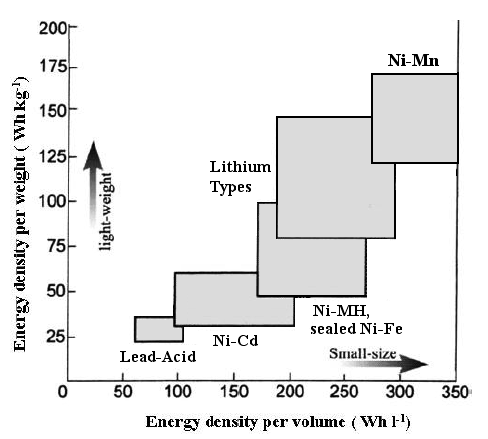

Battery Energy Densities Comparison Chart,

Battery Energy Densities Comparison Chart,

showing the promise of

Ni-Mn catalytic dry cells

with stacked bipolar electrodes.

(...vertical is about right, but it should be way past the right hand

edge of the graph!)

I decided the Ni-Mn battery chemistry looked sound enough

to warrant making a "full size" cell with the 3" x 6" electrodes.

Loosely filling the compactor with 'Ni' mix and compacting it resulted

in

a 20 AH positrode about 4mm thick. A matching 25 AH negatrode was made,

which turned out to be under 2mm, total 6mm per pair. This cell seemed

at first to be a

failure, and the copper framework of the positrode quickly corroded

itself out

of existance. I changed it from a

sealed dry cell to a flooded wet cell and replaced the copper mesh with

a nickel-brass plate. Gradually it started to

charge to higher voltages and drop off more slowly - over a

period of weeks. I almost gave up a couple of times. In spite of using

neutral salt electrolyte the cell

became quite alkaline (explaining the copper corrosion), about pH 12 or

13, but not 14 according to my

pH test strips.

Now after finding a bit more info I think I may

'form'/charge the

electrodes in a flooded tank at higher currents than I've been

able to use in a confined cell enclosure, but then use them in sealed

dry

cells. Manganese is element #25, beside iron #26, and as far as I can

tell, Ni-Mn cells should last as long as Ni-Fe - perhaps a virtually

unlimited

cycle life as sealed dry cells according to the latest Ni-Fe battery

research -

2004,

from India. The

voltage, about 1.9 "nominal" volt cells instead of 1.2 is the big

difference. The

Indian

research found a catalytic device to combine H2 and O2 gasses created

during charging into water, reducing pressure and making sealed Ni-Fe

cells possible for the first time. (I have what I hope is a better,

simpler, cheaper catalyst - antimony, which is mixed into the electrode

material.)

The Indian research also gave a figure for electrode

compaction pressure, something I've been seeking for 2-1/2 years: 4-1/2

tons per square inch for their iron electrodes. My compactor of 1/4"

steel plate bulges noticably

in the middle when the bolts are done up, and I finally bought 1/2"

plate steel to make a new compactor, which will have closely spaced

bolts to exert greater pressure. It should be at least in the ballpark.

I can judge by electrical resistance readings on the positrode, which

are rather high with the present compactor. The "bolt-down compactor

box" is a

key tool for "DIY" battery making without a costly factory.

Chevy Volt: I'm suspicious

What's with the Chevy Volt? Here's a chunk of my opinion:

It's no surprise to me that it

seems to be taking its time getting to market, or that the price is too

high.

The

electric range is abysmal considering its very considerable lithium

battery

pack. In fact, the pack is 16 KWH, said to give an electric

driving range of "up to" 40 miles. (Why then pricey lithium? - you can

get that sort of range with cheap lead-acid batteries.)

The EV-1 on the other hand had a 21

KWH Ni-MH battery pack that gave a range of 100 miles. This

says the EV-1, though it weighed almost 3000 pounds, got about 100/21 =

4.75 miles per

KWH. (This approximates other published figures.) The Volt works out to

"up to" 40/16 = 2.5 miles per KWH - HALF the fuel

economy of the EV-1!

So it uses twice as much electricity from the grid as the EV-1 (or most

anything else) to

recharge. This means it needs a very large lithium battery pack,

driving the retail price way up, to go its very modest distance on

electricity.

What is the problem? It would seem the power train and the

motor itself

must be awfully inefficient. It's a huge induction motor - 110 HP, the

equivalent of at least a 265 HP gasoline engine.

That sort of size should be more suitable for a large truck. Compare

that with a typical 10-30 HP EV motor... and with the 5.5 HP Electric

Hubcap (which admittedly has yet to prove its practicality). And

lithium batteries are inherently not

the best technology for

electric vehicles, though some good workarounds seem to have been

developed... that add even more to the cost. Notwithstanding what's

being said, I'll bet that the Volt's

lithiums will only last a few years (about the same as lead-acid

properly treated with

sodium sulfate), whereas it

looked like the Ni-MH batteries in the EV-1 "would outlive the cars".

The whole effort looks shoddy, even pathetic -- from

the world's biggest automaker, who nevertheless was in deep financial

trouble until bailed out by the public purse on the promise they'd make

electric transportation.

The same shareholders control the nickel-metal hydride

EV battery

company, Chevron-Cobasys (formerly inventor Ovshinsky's Ovonics,

then GM-Ovonics) that made the batteries that made the EV-1 et

al so successful over a decade ago. But since 2001 it

never

makes, sells, further develops, nor (via numerous acquired patents)

permits to exist, any Ni-MH EV

batteries. Of course they won't

restart production and put them in the Volt. That's the last thing

they

want! Electric cars having been forced upon them by a disturbed public,

they've managed to pretend the proven best batteries, cheaper than

lithiums, are no good, and

devolve the whole publicly funded program to this one long delayed

model and rumors of

another

to come from Ford. Where are the

PHEV vans, trucks and suvs? Why are the great, economical batteries

left to rot

--

and where is even basic good engineering?

I believe they want the Volt to be the only, the worst and

the highest priced piece of trash they can make it, as long delayed as

they can hold it back, without attracting a

lynch mob and without having president Obama seek elsewhere for a

solution.

Then, if it ever goes on sale, they'll "phase it out" as soon as they

can get away with it

"because there's no demand."

I also read in the papers ('fraid this is from memory from

a month or two ago) that the Mitsubishi MiEV

electric car "is coming"... but that the few coming to the west (or was

it only to Australia?) this

year will

only be leased, not sold, and that then they will all be recalled and

sent

back to Japan. It sounded like the same thing as in "Who Killed the

Electric Car",

happening all over again - brazenly announced in advance!

They're supposed to be available in late 2011, but I suspect

there

will somehow be further obstacles to

buying one next year. (BTW, the MiEV gets 80 miles from the very same

size

battery pack, 16 KWH, that takes the Volt "up to" 40 miles.)

At the same time, we are shamelessly deluged with TV ads

for

all types of gasoline vehicles, or at best occasionally for non plug-in

hybrids. Seen any of those glowing TV ads for the Volt or any other EV

or plug-in hybrid?

These people, who around 1900 seized control of our

fledgling transportation economy, are not on the same side as the rest

of us.

This enemy within is now fighting desperately to keep electric vehicles

out of the public's hands and by this repetitious TV and other

propaganda to try

to make us

forget there ever was such a thing. The appearance of electric cars or

plug-in hybrids for sale to the public at economic prices would be a

death blow to their giant oil oligopoly, and they'll fight to the death

to prevent it. They shut down, undermine and

suppress

electric car and EV battery development and commercial enterprises as

they make their appearance, and

let the public

conclude from

seeing nothing ever actually available for sale that they must not

really be economically

feasible.

They have waged this war successfully decade after decade. How long

will we

continue to let

them dictate to us that we shall burn fossil fuel, with wanton

inefficiency, for all our transport needs?

Hah! That was going to be the end of my tirade, but here's a great

epilogue:

a typical example.

Someone has sent me a link to Evergreen

Electric Vehicles - with a promising looking electric car "about to

be

introduced" at the 2008 Seattle Auto Show. This "medium speed vehicle"

(up to 60 Km/H) must have been the product of much fine development

work, and there are videos of it driving around, beautifully. Whether

or not it ever made

it to the show, it would seem it caught the attention of the enemy: the

web

site was last updated in 2008. It's full of great reports and

good news that, as always, abruptly ends with no explanation.

If president Obama had given any portion of a billion

dollars to this Washington company (and provided it and its key

personnel with protection against corporate, financial and physical

violence), these cars could well be in production, on the roads, and

probably in high demand with a big waiting list by now.

Their web site: www.evergreenelectromotive.com/

The Evergreen 2008 EHC

The Evergreen 2008 EHC

When people see one individual

company, idea or person disappear, it's puzzling, but the

obvious conclusion is that something individual happened to it - its

business

plan was poor, financing didn't come through, the product was

uneconomic or bad circumstances forced it out of business, or perhaps

the head of the company had some sort of personal or family trouble or

an accident. But various such

companies, some with "corpse" web sites, can be found -- and where are

the successful ones, electrifying our transport system? For example,

try looking up companies doing

nickel-zinc batteries. There were two or three when I looked a while

back, also a flat-plate Ni-MH battery company, all with nothing recent

on their sites and no explanations. The ones I tried don't answer

e-mails. Why would all these various people go to all the work of

developing products, creating companies and web sites, and then just

vanish on the eve of commercial production?

And what happened to the people who invented engines that

run on compressed air a couple of years ago - two independent designs

in

two separate countries? And the big, safe plastic compressed air tank

whose side would just rip open and release the air if it was hit or

punctured? "Now we don't need to burn fossil fuel to drive cars any

more." they said on TV. But where are the cars running on air? What

happened to the

entire promising technology? The engines worked. Everything was going

great -

until they hit the TV news. The first news was also the last.

And whatever became of all those electric car companies

that started in the 1970's with the US "oil crisis"? Popular Mechanics

magazine et al were raving about them and detailing their features, but

I don't know of a single

electric car having actually been sold in that era. I met a person who

invested in one of them after an electric car ride, saying "This is the

future!" and he said "Nothing happened. It just never went anywhere."

He was certain there had been interference.

History has recorded the "disappearance" (read murder) of

Diesel from a ferry, the burning (read arson) of Edison's Ni-Fe battery

factory and the

nefarious dealings of GM with Constantinesco to ensure his fuel saving

mechanical torque converter was never used, but it would sure be nice

to know what happens

to all these

other disappeared companies, and to the inventors and product

developers that

created them! I bet one could

look back and find the decades are littered with sabotaged attempts to

introduce

non-petroleum transportation and better electric car batteries, each

naive startup wondering why no one else had already done it.

We can eat all the best

food we want, and try different diets,

develop new multi-vitamins, be nature-friendly or whatever, but it's

hard to make

transportation healthy unless people start to realize there seems to be

a huge tapeworm within, clothed with money and power but somehow

swallowing everything good and... according to what I've heard...

spitting out the evidence in mid ocean from tankers, in

45 gallon

oil drums filled with cement.

Mechanical or Magnetic Torque

Converter Project:

The Quest for Torque Leverage Without Gears

Last month's magnetic design seemed to do all the right

things... but with so little force it seemed impractical to try to up

it to car moving magnitude. So I went back to the clock escapement

idea, and I had a

design in my head by the end of June. I sketched out a modified design

July eighth, then made a modified version of what I'd sketched.

For the rim of the output drum, I ended up cutting 37

slots between 37 solid "sprockets", each element 1/2" wide. I cut slits

in from the edge, and simply bent out the pieces for the slots. I

elected not to do this to the rim of the drum itself, which had proven

so handy for so many of the TC designs. When I curved it around the

drum rim, it looked like a crown of some sort. It also didn't quite fit

and had to be trimmed down to 36 teeth and slightly spaced in from the

rim.

I had thought of putting 12 very short escapements around

the rim, but finally opted for the idea of six somewhat

larger ones.

Next I made a

plastic escapement piece. I had finally

realized that its two hookes don't have to be at opposite

sides of the drum, merely that one point be at a tooth while the other

is 1/2 way between teeth, that they be angled appropriately for

wherever they were, and that they should pivot as near to the rim as

feasible.

Then with the fit of the triangular "hookes" I realized

that the sprockets should really be 'points' - vertical lines - rather

than occupying 1/2 the space around the rim. Rather than cut the

aluminum thin, I twisted the sprockets with a pair of pliers. This

achieved the same effect against the triangles without leaving thin,

brittle teeth. One broke off while I was twisting it anyway, and 3 or 4

more were much weakened.

The whole thing seemed a bit hokey and it now looked a bit

like a giant bottle cap. Nevertheless I persevered. I cut a metal

escapement out of 1/8" aluminum using the plastic one as a template,

and

when I'd cut down the points until it didn't jam everything, it rattled

back and forth as one rotor was rotated against the other.

Left: Torque Converter drum with "crown" of twisted sprockets.

Left: Torque Converter drum with "crown" of twisted sprockets.

Right: Motor rotor with flanged axle and the first three prototype

"escapement anchors".

The washers hold the drum at the right height for the escapements to

mesh

with the sprockets.

Fish scale hanging down was to measure the torque.

The torque should vary by the square of the speed

difference between the two rotors. Either unit could be turned "freely"

at very slow speed, but at a fairly low speed the driven rotor pulled

the other around with a force of around 1 pound.

With the two anchors (the second one being heavier), the

force seemed to be around 4 pounds at 30 RPM. (Although I had a fish

scale to measure the force, the unit repeatedly jammed and it wasn't

possible to get a steady reading.) However, boldly extrapolating

anyway, that would be 16 pounds at 60 RPM, 64 pounds at 120 RPM, 256

pounds at 240 RPM, 1024 pounds at 480 RPM, 4096 pounds at 960 RPM, and

16384 pounds at 1920 RPM. That, of course, would be assuming that

nothing busted, wore out, or jammed! And the motor certainly won't

supply thousands of pounds of force, ie, it surely won't have the power

to attain those highest RPM differences. (Wasn't the Avro Arrow engine

20,000 pounds of thrust?)

I looked at the various angles and shapes of the third

prototype escapement, and started to see there was a "correct" shape,

and

that it was shaped "wrong". The square part of the edges was sometimes

able to meet the sprockets instead of the triangle edges because there

was nothing to specifically prevent it. This was the main source of the

jams. The right shape wouldn't be able to pivot into a position where

it could jam. A "wrong" shape could be made to work by attachments that

would limit its travel, but with a "right" shape, that would be

unnecessary. If I hadn't made the unit and the parts, I wouldn't

have realized there was a "right" shape and any number of

"wrong" shapes.

In a couple of days I had decided not to make the rest of

the escapements and proceed to powered trials with the "crown" gear. It

might well be that I would make them all and then have to almost

immediately make slightly different new ones to fit a new sprocket

gear. Once I

had an idea for a better sprocket gear, it was: gear first!

On the 15th after making the spot welder, I cut a new

strip of #12 aluminum, and then made a punch and die to punch the

aluminum gear teeth the way I wanted them... which was similar to the

way I had in mind in the first rough drawing except for punching them

with a 45º twist as I had done with the crown. The

differences

between this and the crown are:

a) the flats between the angled parts are retained for

strength. This will also prevent the tips of the escapements from

swinging in farther than they're supposed to - a cause of jamming of

the "crown" gear unit.

b) the holes are punched from the center of the strip and

are supported

both top and bottom - also stronger.

c) I intended to use a special punch and die jig with the

strip clamped down while punching, ensuring uniform, straight sprocket

teeth with even spacings between them.

In concept I wanted 45º triangle teeth: /\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

. These would have been hard to do with sheet metal. ( - but probably

not

impossible. I was thinking that they'd have to be milled from a thick

piece of aluminum, but some jig to form it from sheet metal could

probably be created. Hmm... hmm...)

In practice: _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ _/ with 45º

angles and the same

spacings between points should work pretty much the same, though it

will

probably wear out faster. How fast remains to be seen. Could be a

minute or five years for all I know so far. The escapements, their

triangles also 45º, will hit pretty squarely against the edges, so

they might last much longer than one would suspect at first glance -

and how long solid aluminum triangles would last is also unknown.

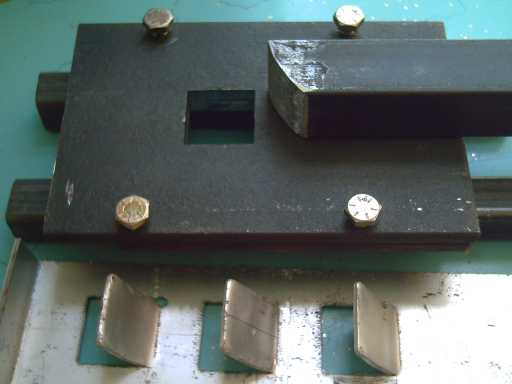

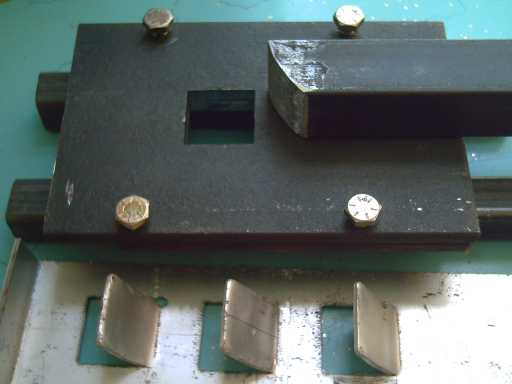

First, small sprocket punch (.5" x .5")

First, small sprocket punch (.5" x .5")

The main components of the second, larger sprocket punch & die

(1" x 1")

The main components of the second, larger sprocket punch & die

(1" x 1")

The punch at work

The punch at work

Later two "rails" were added underneath so the punch could be used

on a flat surface

Later two "rails" were added underneath so the punch could be used

on a flat surface

without the teeth hitting it as they were 'extruded'.

(The astute and long-time

reader of these newsletters may

recognize that the die is made from the cut-off ends of the original 3"

x 12" battery electrode compactor, left over when it was reduced to 3"

x 6". It was handy with four holes pre-drilled and threaded.)

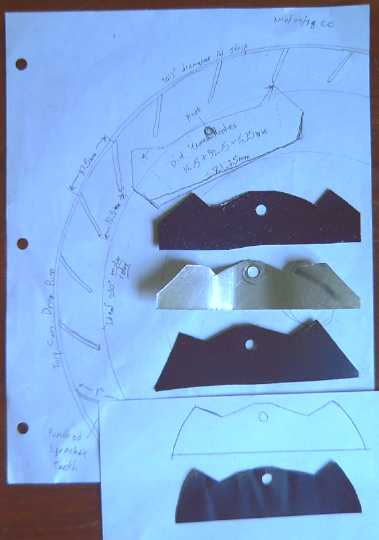

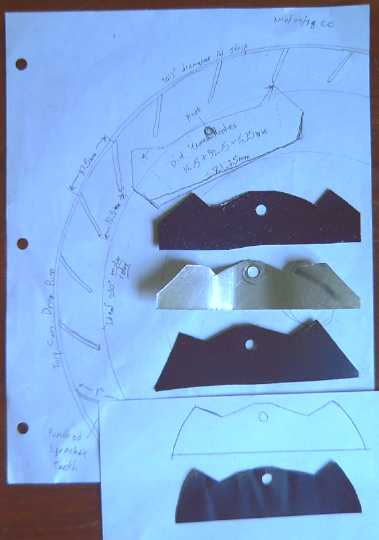

L: 37" sprocket strip of .081" (#12) sheet aluminum with 25 teeth,

ready to bend into a ring sprocket-gear.

L: 37" sprocket strip of .081" (#12) sheet aluminum with 25 teeth,

ready to bend into a ring sprocket-gear.

R: Escapement piece shape trials. I finally realized they had to be

curved to account for the pivotting.

The large size teeth had their own problem: they stuck in

too far and hit the 11" diameter motor rotor - and extended to the

holes drilled

and tapped for the escapement pivots. It was necessary to mount things

so the teeth were slightly above the rotor, which fortunately wasn't

too hard to do with some sanding and by inserting some washers. I also

had to drill new pivot pin holes at a lesser radius from the center

axle.

However, for a 10"/300mm diameter rotor as I now recommend

for the motor rotor (eg 6129R),

it would be a very good fit. It makes me want to run off and change

everything

to match my vision of "as ideal as stock parts intended for something

else can get"! But I decided to leave that for motor version four since

I had other things to do, and instead (sigh) drilled another six holes

in the 11" rotor.

Rotor on axle, with 3 pivoting escapements, output drum with

sprocket strip, nylon "pipe" for bushings (inset).

Rotor on axle, with 3 pivoting escapements, output drum with

sprocket strip, nylon "pipe" for bushings (inset).

It was hard trying to center the hole in the nylon rod... until finally

I remembered I have not only a drill press but a machine lathe!

It would be nice to eliminate the 12" frying pan as being

a

hard to get "custom part", and it occurs to me this can easily be done.

The torque converter drum could be made from two flat

pieces

by cutting a 12" circle of thick aluminum plate (3/8" or 1/2" thick?),

making the necessary

center and bolt holes, and then screw the toothed strip (as above) into

its edges. Optionally, an untoothed strip could cover the toothed one

to add stiffness and perhaps keep dirt out.

Or, perhaps better, a thinner circle plate could be used,

eg 1/4" or 3/16". One widened edge of the gear strip would be slotted

with "V"

slots and the tabs thus formed bent over inwards to 90º, level

with each other. This edge would be screwed onto the flat surface of

the plate all around the rim.

To get the aluminum plate round and true without a big

lathe - one able to hold a disk over 12" in diameter - it could be cut

roughly

to shape with the center parts cut and drilled, and then spun on the

motor itself to mark where to file down the outside edge to true it...

or perhaps even hold the file or some tool at the edge with the motor

turning,

though safety and technique I'd have to leave up to the user on that

idea.

On the 31st I finally had the drum and the first three

escapement pieces about ready to try, after hours of grinding, filing,

sanding and burnishing, trying to adjust the dimensions of the

escapements so they would toggle as smoothly as possible without excess

play that would have them "banging" on the teeth, but without jamming.

But when I tried it, again the force developed was wholly

insufficient. It would take more than adjustments and fine tuning to

make it work.

I'm now thoroughly sick of trying to employ the principle

of forcing masses to go back and forth at high speeds. It worked for

Constantinesco, but I'm beginning to think it takes a lot more mass,

making much more oscillating motion, than there is room for in an

"Electric Hubcap".

There has to be some simple way to create some

direct

link, something like variable gears where if "A" moves, "B" is

forcefully pushed, not indirectly coerced by an oscillating mass that

will shove

out of the way with less force than it takes to turn the car wheel.

But, now, if those same escapement pieces were being

directly shoved back and forth by the motor rotor instead of

oscillating freely, their

back and forth motion would forcefully, and smoothly, shove the same

ring gear and hence the car

wheel around... hmm - I see the glimmerings of a new plan! ...It'll

need

more pieces... Maybe it's

time to go study more aspects of mechanical clock mechanisms!

Capacitive Discharge Spot Welder

Project

Need to Weld

One of the recurring problems I've had trying to do batteries is to get

the electrodes connected to an external terminal, through a sealed

case. Solder (probably hard

solder as well as soft) corrodes away - and probably isn't a good

contaminant inside the battery. Regular welding would destroy the

pieces.

On the 15th I phoned

around to see if anyone in town was selling spot welders of the sort

commonly used for battery tab

spot welding purposes. Nope! So I

decided to check into what went into the makeup of one. At first I had

planned to visit a welding supply shop and start asking around, but I

was dubious anyone would know much about this specialized type of

welding - then

it occurred to me to check the web.

It seems the essence is a discharge of capacitors that

creates a sudden very high current through the two welding electrodes

and into the parts to be welded. The resistance to this massive current

flow is highest at the point where the two pieces touch, and the sudden

heat there simply melts the two parts

together, creating a "nugget" of weld material. So it's also called

resistance welding. Higher resistance metals like steel and nickel work

better

than the best conductors like silver, copper and aluminum, as the heat

generated at the spot to be joined is higher and melts more metal. The

electrodes, simply fat solid copper wire (eg, #4) with cone

shaped ends, were placed, then a foot switch activated the discharge. A

100-300 amp SCR is used to switch the power. However, it seems the SCR

limits the current considerably, and much more capacitance is needed.

But the whole switch arrangement can be omitted. Then the instant the

second electrode make contact the arc happens. Much skill is

evidently required for this technique.

There were commercial welders (2K$+), two-pulse welders,

welders with sophisticated solid state controls, welders made with

microwave oven transformers, electrodes which activated the pulse when

they reached a certain pressure against the workpieces, and other

refinements. One to 4.5 farads of capacitors(!) are typically used.

But the key is the spark. Discarding all sophistication, I

soldered together a rig

with four 2500uF capacitors, two leeds with alligator clips to attach

to

a 12 volt power adapter, and two leeds to the electrodes, which were

just solid #10 copper wires with the points sanded into a cone shape.

This actually made a battery tab sort of stick to a

battery. So I went out to get more capacitors. I bought two dozen

4700uF/25v ones at Queale Electronics, total 0.113 farads. Those were

the biggest they had except at very low voltage ratings. (This was all

before I discovered the massive "one farad plus" ratings others were

using. They say "try ebay" to find the capacitors.) I soldered them to

two bus

wires of #12 gauge copper wire. This turned out to be rather thin - #10

or even #8 would have been better. My unit is powered by a dinky 12VDC

power

adapter, but it's the massive current pulse that welds.)

(Be sure to get all the capacitors the same way around,

and

to hook them up the right way around every time. Polarized capacitors

connected backwards can explode with quite a bang. You could put a

diode in series with the power adapter line resistor to prevent

backwards hookups.)

I was using #16 wire about 3 feet long to the electrodes.

Results seemed unsatisfactory, and I checked on the web again. Someone

linked via youtube was boasting about how his (rather complex) welder

was only 500 micro-ohms and so could out-weld commercial models.

Another person mentioned switching from 3' of #10 to 3' of #8 and

getting better results. (I also learned that the "nugget" tends to form

towards the "+" side of the join. The positrode should go on the

thicker or lower resistance piece.)

I switched to very short #10 stranded wire electrode

leeds. It made

all the difference! Hmm... ultra-flexible #8 audio wire would be nice.

The device can still only be used to tack very thin

pieces together. I tried #26 nickel-brass and couldn't make it stick

(my battery electrode plate thickness), but when I thinned a piece in

the rolling mill (or use a hammer) to ~1.5mm (.005"), I could weld it.

The technique that seemed to work best was to press the

parts together with the positrode and then firmly tamp the negative

down onto the work, preferably but not necessarily quite near the plus.

The force with which the contact points are pressed together is

important, with too much force leading to too little heat and no weld,

and too little causing holes to be burned through the thin tab piece.

Naturally a pit is made in the work where the negatrode

touches down. (See the pitted practice battery in the picture.) I can

see how the foot pedal would be better... but this simple unit

basically works, and

can be made cheaply and quickly.

(Reading later, I see it's best if the negative is

on the thin tab piece rather than the positive. This guy seems to have

the good stuff and good info: http://frikkieg.blogspot.com/

. Seems his welder has 4.5 farads of capacitors(!), so I was on the

right track using so many myself... but underpowered!)

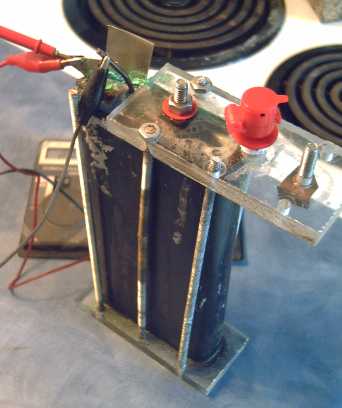

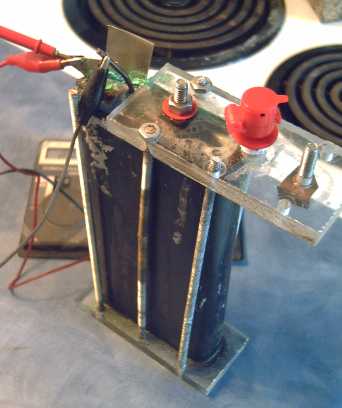

The primitive spot welder:

- 24 capacitors totaling 112,800uf (@ 25V).

- two electrodes - #10 wire.

- two clip leeds to 12 - 18 volt power adapter (observe polarity!)

- resistor (I used 3.3Ω/5W) to limit charge rate from power

adapter,

and

limits

current after initial spark.

- the fatter the wires in the discharge circuit the better.

Note

electrodes attach at center, not at an end: 1/2 the current flows

through

each side of the buss wires.

Welding practice: welded rag-tag end of a battery tab to 2nd battery -

note all the pits in the battery case where the negatrode touched

after placing the positrode on the tab at the weld point. Though it has

acquired a couple of extra holes and pits, the tab is well stuck on!

Sunglasses might have been better than just "UV blocking" glasses for

the sparks. But I soon started simply looking away before connecting.

This was quite a satisfying little project with other

projects

dragging on and on - a successful prototype in about 4-1/2 hours

including this writeup. (...writeup later expanded.) I may of course

try to

make further improvements later

to weld thicker pieces.

First Improvements: By evening I realized I could cut the

capacitor assembly in half and put it in two rows, and attach the

electrodes to both rows in the new middle. This would double up the

"skinny" #12 wire busses to give the effect of #9 wire instead. In

fact, I would only cut one wire, and fold the other one back, to make

it two rows. Say, maybe 3 rows of 8 would be even better!

I'm not sure whether adding 8 more capacitors (4 rows of

8, 0.15 F?) or getting the effect of thicker wire would have greater

effect. Certainly going from 36" of #16 wire to 10" of #10 for the

electrodes made the difference between failure and success at least

with small, thin pieces. Of course, I could do both. And I could

go up

to about 20 volts, but 16 volts from the "12 volt" power adapter seems

a more comfortable margin for 25 V rated capacitors that are being

asked to do a very hard job.

In lieu of remote activation of the pulse, a means to

prevent pits in the workpiece might be to clamp a piece of copper to

the work. Bring the second electrode down on the copper and pit that

instead. Being a low resistance, it should pit less. (Just setting the

copper on the work doesn't make a good enough connection - I tried it.)

Before month's end, I put all the above improvements into effect,

using short lengths of "#8" (really #9 ...if!) very flexible audio wire.

A 12 volt, 1 amp power adapter, hooked to the alligator clip leeds,

takes a

few seconds to recharge

the capacitors for the next zap. (In theory, the series resistor should

be 12 ohms or more.)

Copper isn't the best thing to try to

spot weld - I didn't manage to

weld the copper

electrode mesh shown to its leed wire - only to burn off some

pieces of

the mesh.

It did weld a couple of nickel or nickel-brass battery tabs quite

nicely, though if I pulled

hard enough,

all the welds broke off before the tab metal ripped. (With commercial

battery tab welds,

it's about 50-50 in my experience.)

Turquoise Battery Project

Summary

As happened a couple of months ago, I've done so much work

and writing on this project it's become a long, tedious and somewhat

disorganized report.

This time, I'll leave the text as there are many details of potential

interest to anyone working on batteries, but I think this shorter

summary just touching all the key points

is in order.

Chart shows the promise of Ni-Mn EV battery chemistry with proposed

constructions:

sealed dry cells of bipolar electrodes stacked to any desired voltage

with catalytic recombination of H2 & O2 into H2O.

Later calculation (after only a guess for the graph) showed the

horizontal placement

should have been entirely off the right hand side

of the graph: 500-750 WH/L...

and so are Ni-MH or Ni-Fe dry cells (350-560 WH/L).

The rather 'hacked' test battery under charge.

Both electrodes contain a mix of Ni and Mn for

different reasons. In fact, if one makes a positive electrode of 60%

Ni(OH)2 and 40% MnO2 'additive', it has about equal amp-hours whether

used as a positive or a negative electrode.

AFAICT, it seems the biggest difference between Ni-Mn (2.5 open circuit

volts) and

Ni-Fe (1.35

volts) is the need to add a bit of egg albumin to the manganese

negatrode in order to raise the hydrogen overvoltage to handle the

higher reaction voltage.

And this month, I was pointed to a fabulous 2004 research

report from

India on new sealed Ni-Fe batteries [www.nickel-iron-battery.com],

which mostly looked equally applicable

to Ni-Mn. A few original Edison flooded Ni-Fe cells are still in use

today almost 100 years after they were

made.

I decided to make my "full size" Ni-Mn battery with 3" x

6" flat

electrodes, which turned out to contain material for about 20 amp-hours

in 4mm (Ni+) and 1.5mm (Mn-) thick electrodes. I used copper mesh

collectors and leed wires. I started

with a "dry cell" with limited electrolyte, but the pressure rose

rapidly. (The sealed case worked great!) But I soon flooded it and

vented it, and found it would handle

much more charging current - hundreds of milliamps instead of tens.

Later, after reading the report from India, it looked like the best

thing was to initially charge the negatrodes separately in a flooded

tank, and then

use them in sealed dry cells.

A new catalytic technique to recombine O2

and H2 into water was employed that kept pressures remarkably low,

which would allow much larger sealed cells than are currently

practical. Their catalyst, however, uses platinum, which is pricey

stuff (and cerium). I hope to find one that uses economical

ingredients, like

antimony oxide.

The report also mentioned 675 Kg/sq.cm. (4.8 tons/sq.inch)

as an "optimum" electrode compacting pressure for their

iron electrodes - finally!, the first

actual figure I've ever seen on the subject. I probably get around 1/2

that in the

bolt-down compactor.

It further mentioned use of PTFE (teflon) suspension as

binder paste to "glue" the electrode together. This is probably better

than "CMC gum" and I'm trying to buy some. Seems the only place to get

it is China.

I am also wondering if it's possible to find some inert

but electrically conductive or semiconductive organic 'binder'

substance that might be both 'glue' and increase the conductivity of

the electrode, giving high current potential. Maybe that's a pipe

dream, but it would be great if a

small battery would, for example, start a car engine.

Although I used neutral pH KCl salt electrolyte, hydroxide

liberated by the charging reactions turned the cell alkaline, about pH

12 - 13. (That's still somewhat less caustic, and using edible salt

saves you from

having to work with

"caustic potash".) In the alkaline environment, the copper collector

plate and leed of the manganese negatrode were fine, but the copper in

the nickel positrode soon dissolved into green goop. Even the stainless

steel terminal bolt had some nasty corrosion. I put in a piece of

nickel-brass for a collector plate, which is faring better but not

well. By month's end there was green goop everywhere in and around the

battery. (proving it's a green energy battery!) I eventually took some

copper mesh

and nickel-brass wire to Victoria Plating and had them nickel plated

for

$70 - a bargain after the prices I'd been quoted for any sort of actual

nickel metal product. I'd rather have taken stainless steel mesh as

being naturally more resistant, but they told me that can't be nickel

plated. It then occurred to me that painting an alkaline earth element,

hmm... barium carbonate?... preferably the hydroxide, but it's hard to

make, on a

positrode metal might help protect it from alkali, so that pure nickel

might not be

necessary. Until now, only pure nickel has been made to work in

alkaline positrodes, but there may be another way. I'll be

experimenting with that.

The cell took the whole month to initially charge, and in

fact it's still charging. I

almost gave up more than once. It would go for a couple of days

sometimes without there seeming to be any increase at all, then the

third day the voltage would be a bit higher and it would hold it a bit

longer. By the end of the month it would

hold over 1.8 volts for a few minutes, and the figures were still

slowly rising. I'm wondering how much hydroxide is being converted to

carbonate via CO2 in the air with an open top for so long -- and when

that and the corrosion of the positrode plate will overtake the

charging and improvement will stop. I think all

the "green goop"

corroding off the

positrode, and perhaps impurities from the CMC gum or impure pottery

supply chemicals, is making for (as usual) very high self discharge,

and that

when everything is pure and right with nothing corroding away, it will

hold charge fine. Initially charging the Mn's in a tank should be

considerably faster and soluble impurities would dissolve out.

Again, along with the chemistry and tests is the idea

that bipolar electrodes with no collector plates could be stacked

inside to

create dry cells of any desired voltage in a single cell of almost

"ultimate"

energy density. It would also be cheapest. The edges could be sealed by

dipping the complete

assemblies in (take your choice) paint, glue, epoxy, wax... hmm,

preferably something rubbery and flexible for when the nickel 'trodes

swell a bit.

Cross Battery Checkup

I cross checked the graph figures by weighing and

measuring an actual Ni-MH battery. That should have similar amp-hours

to Ni-Mn but at 1.2 nominal volts instead of 1.9. The nickel side

is the same, and Mn gives similar amp-hours by weight to very good

metal hydrides, and the figure is in the same range as the theoretical

calculations.

The 30.5 gram Ni-MH "AA"

cell contains almost "nothing

extra" and so has almost "ultimate" energy density: 2.6 AH * 1.2 V /

.0306 Kg = 102 WH/Kg. Now account for the voltage difference: 102 WH/Kg

* 1.9/1.2 V = 162 WH/Kg. The

vertical placement of Ni-Mn on the chart

is thus approximately borne out.

An older 1.6 AH Ni-MH cell

weighs only 25 grams instead of

30, which actually accounts for almost 1/2 the difference in capacity.

1.6 AH * 1.2 V / .025 Kg = 77 WH/Kg. (not 63 WH/Kg)

For energy by volume, which I haven't tried previously to

work out, the "AA" cell measures 14.4mm (diam) * 49mm ("+" button not

included), or 5.54cc. 2.6 AH * 1.2 V / .00554 L = 563 WH/L. That's

already off the chart. Multiply that by voltage: 563 * 1.9/1.2 = 892

WH/L. Since the case will be thick plastic rather than thin metal, it

won't do quite this well, but it certainly seems I should have tried

working it out before I made that chart - these are not going to use up

a lot of cargo space! The 1.6 AH Ni-MH fares worse here: 1.6 / 2.6 x

563 = 346 WH/L. That's the only figure that's on the chart's horizontal

scale. An equivalent Ni-Mn is hardly likely to be under 500 WH/Kg,

thick plastic case and all.

I plan to try out many ideas and materials in the coming

months - starting with a more powerful electrode compactor, hoping to

get better conductivity within electrodes.

(This month's full gory details follow.)

Ni-Mn Battery

with "Full Size" Electrodes

The positrode I so casually grabbed to mate with the Mn

negative for a test battery in May turned out to be the last lanthanum

perchlorate electrode when I checked into it, rather than nickel

hydroxide. Oops! I was fooled by the greenish colour, forgetting that

not only nickel hydroxide is green, but the perchlorate is almost the

same green - slightly brighter. The battery as such didn't hold charge,

but I did find out that the manganese negative didn't seem to bubble

a lot of hydrogen.

The chemistry looked promising enough that I decided to

make a Ni-Mn battery

with my planned "full size" 3" x 6" electrodes, the size of the

compactor.

I would find out how much material makes how thick an

electrode, and hence obtain a much better approximation of how many

amp-hours to expect from what size and weight of battery.

Nickel Positrode

I decided to try for 50

amp-hours. Nickel hydroxide is 289

AH/Kg if the valence change is 1.0. With the manganese additive raising

the oxygen overvoltage, the nickel valence is said to go from about

2.25 to as high as 3.8, a change of 1.55, evidently with a considerable

proportion

of NiO2 present in the charged product. (Below valence 2.25, the

conductivity becomes poor. My batteries are starting with straight

Ni(OH)2

at valence 2.0, no doubt explaining some of the high internal

resistances.)

There is a fair level of uncertainty of what valence the

nickel will

actually attain with salt in the electrolyte. Having no special

equipment, I can only measure the amp-hours attained in a successful

battery and adjust formulations based on the result, a process so

laborious I'm unlikely to define an "optimum" mix as part of the

project.

I decided on these ingredients:

Using 1.5 valence change as a working basis, 50 AH / 433

AH/Kg = 115

grams (of Ni(OH)2).

Using half as much MnO2 as Ni(OH)2 (33%:67%), 57.5 grams

Using more monel powder (by weight) than Ni(OH)2 for good

conductivity, 125 grams.

Adding 1 wt% (of the Ni & Mn) Co2O3 for even more

conductivity, 1.75 grams.

Using 1 wt% (of the total) CMC gum for 'glue' to hold the

electrode together, 3 grams.

About 70 cc of water.

Some Notes:

* I forgot to put a thin layer of calcium hydroxide on the

collector screen as I've done with a couple of previous positrodes -

a possible way to protect it from corrosion besides making it of

nickel? I'd like to try barium hydroxide, but it seems harder to make.

It might

even help to protect the metal collector plate/leed wire structure.

* I think I'll also add the 1% antimony oxide to the positive electrode

next time, as another possible way to reduce gas pressure by causing H2

and O2 to recombine into water.

* It's amazing to start with mostly turquoise green nickel

hydroxide, mix in a couple of black things (MnO2 & Co2O3), and end

up with black - no hint of green.

* I suspected that 125g would be more monel than needed,

which

would needlessly lower the AH/Kg of the battery, but since poor

conductivity seems to have been my biggest problem so far, I just hoped

that would be 'lots'

and it would work well.

* But it turned out that the dry electrode initially had

resistance of tens of kilohms. That was completely uncharged.

Perhaps when

the Ni(OH)2 reaches a valence of 2.25, it will be considerably improved.

* Also the readings are suspect. When the ohm meter

automatically changes ranges, the apparent resistance 'jumps' by an

order of magnitude. Still, it's nothing like ohms or tens of ohms.

* I've mentioned discharging NiOOH to beta Ni(OH)2 with

H2O2. The opposite

is to charge it to NiOOH, using NaClO (bleach). I sprinkled a few drops

of

bleach to absorb in, to see if that would result in lower resistance

readings. It did seem to help, though it wasn't a big

improvement.

* I used a copper mesh and a #10 copper leed wire. The leed connected

to

a stainless steel terminal bolt. The same arrangement was okay on the

negative side, but the wire corroded right through within a day or two

in the positrode. Furthermore, where copper touched the bolt, the

stainless steel too

was corroded.

When I made the electrode from the mix, only about 40% of

the 50 AH worth of loose mix fit into the compactor with 1/2" sides. It

compacted into

a 20 amp-hour electrode 4mm thick, 145g. (140 AH/Kg. If it wasn't for

needing the rest of the battery, that would be great! The monel drags

the figure down considerably.) I could probably

up that to 30 AH, 6mm thick next time if the conductivities are good

once it's charged. Apparently a battery of 60 amp-hours equivalent to a

100 amp-hour lead-acid battery will be larger than I visualized last

month.

Since I had more than 1/2 the mixture left over, I made a

second 4mm electrode briquette, with no collector screen (134g -

remarkably within a gram of the same weight as the first without its 11

gram collector screen), to be part of

a central bipolar electrode for a higher voltage battery. My case was

fat enough for two sets of electrodes of this thickness - would I dare

try a 4

volt battery instead of 2? (I didn't.)

Depressing News:

the Hydraulic Press gets Bad

Press

...the bolt-down compacting system is Better!

When I compacted the electrode with the new 12 ton

hydraulic press, I pumped the handle until it took an awful lot of

force to push it any farther. I pressed in the middle of the electrode,

somewhat towards each end, and then the middle again. The powders

compacted from 1/2" thick as poured in down to about 4.5mm. The

electrode seemed pretty solid, but for comparison I dug out the bolts

for the bolt-down compacting system

and torqued them down. The electrode went down about

another 1/2mm to 4mm thickness.

It seems my bolt-down electrode compacting system is

better than a 12

ton hydraulic press! Evidently the only point to buying a hydraulic

press was to demonstrate this point. A 45 ton press might achieve

about the same results as the bolt tightening system... for $2000 more!

To speed up the labourious bolt-compacting process,

perhaps all I needed was an electric nutdriver, and a holder for the

compactor so I could work the driver without having to hang onto that

at the same time?

A 4.5 amp drill might hold a nut driver bit quite nicely,

and it has a lot of torque. I tried that next.

One thing I'll do differently if I make another

bolt-down compactor will be to use a 7/16" or 1/2" steel plate for the

bottom, as the 1/4" thick bottom plate bulges a bit in the middle. I

may change this regardless. The

1/4" top plate also bulges, but it pushes down the 3/8" thick x 3" x 6"

die

piece onto the electrode, which piece (I trust) doesn't flex.

Another thing would be to have even more bolts around the

edges - at least one per inch.

I'm also wondering now why I decided to reduce "full size"

electrodes from 3" x 12" to 3" x 6". Although they'll each be somewhat

easier, it means making and installing twice as many batteries to get

the same result.

Manganese

Negatrode

I decided to go with a larger amount of almost the same mixture as last

month

for the negatrode, but with just a little of the finer nickel particles

as derived from the

hydroxide. Since I'd used 40 AH worth of positive material and since

the battery should be positive limited (so it creates O2 when

overcharged rather than H2), perhaps making about 50 AH for two

negatrodes

would be about right:

Expanded copper mesh collector sheet/backing with Cu leed wire, 6" x 3"

(11.8g)

Monel alloy powder - 55g (conductivity, ??)

Ni(OH)2 - 5.0g (conductivity - reduces to Ni)

MnOOH (?) - 55g (active ingredient - overdischarged state)

Mn metal powder - 20g (active ingredient - charged state - add this

last)

Sb4O6 - 1.25g (increases hydrogen overvoltage)

CMC gum - 1.35g (glue)

Albumin (egg white) - a smear (significantly increases hydrogen

overvoltage even in PPM quantities)

HOH distilled - 15cc

Assuming the Mn has in fact been successfully reduced from

MnO2 to MnOOH, the balance is 30g of Mn overdischarged to valence [III]

and 20g charged to [0], with [II] being the expected discharged state.

It should thus take 15g of Mn to bring the 30g of MnOOH up to "normal

discharged" state, leaving 5g of 50 charged. Since the nickel side was

40 AH, that should also leave 5g of uncharged Mn(OH)2 when the positive

is fully charged. Assuming gas permeability, the migrating O2 from the

"+" side during overcharging will spontaneously discharge as much Mn as

is needed to prevent the "-" from overcharging and generating hydrogen.

One might question whether there's any value in having

undischarged manganese in the negatrode when the positrode is fully

discharged, and also whether 5g, 10% extra, is enough uncharged

material during overcharging to prevent hydrogen generation. I'm not

going to try to answer these questions at this point.

Afterthoughts:

* I found out this month that the best way to charge the negatrodes

is probably immersed in a tank, with nickel plate positives bubbling

oxygen gas.

They're put into the battery later. That means the initial state of

charge isn't important. Thus pottery supply NiO and MnO2

(assuming purity is okay) are probably as good as powdered metals, and

they're cheaper and more readily available.

* Quantities should be adjusted to account for the oxygens. (I do

wonder if the electrodes should be re-compacted after charging,

especially if the compaction pressure was low to start with. Of course,

the electrode needs space to hold the manganese hydroxide when

discharged, too - but one wouldn't discharge the Ni again of course...

or the copper mesh!)

* In the past, it has been considered that a sealed alkaline cell

should be positive limited on charge so that if overcharged, oxygen is

formed first and is converted back to water by discharging the metal

[manganese] to hydroxide at the negatrode. Generation of hydrogen,

which there was no way to eliminate, was thus prevented regardless of

overcharging. With the catalytic recombiner, it would seem more

desirable that both O2 and H2 start to be generated at about the same

time for catalytic conversion, rather than to have one or the other

form first and build up pressure. The research paper had negative

limited cells. I'd guess that equal capacities would be ideal. The Ni

side valence only goes down to 2.25, about 5/6 discharged, before the

user will decide it's not putting out very well, and it would be the

same for the Mn side, 5/6, if it had the same capacity. Thus the usual

desire to have some reserve negatrode capacity would be in practice

fulfilled.

The Mn negatrode reaction, one with the elusive

solid-solid (non-dissolving) reaction products on both charge and

discharge:

Mn(OH)2(s) + 2e-

<=> Mn(s) + 2OH- [-1.55

V; 976 AH/Kg or 1513 WH/Kg of Mn]

I neglected to weigh the electrode (with screen and leed

wire) before installing it, but it should have weighed about 81 grams.

The thickness was about 1.5mm.

Add the 145g for the positive and it's 226 grams for 20 amp-hours, or

88 amp-hours per kilogram. Since it's two volts, that's 176 watt-hours

per kilogram, considering only the electrodes. Add to that the case and

the electrolyte.

The center electrodes with no collector screens or leed

wires are about 25 grams lighter, 201 grams or 99 AH/Kg, 198 WH/Kg.

For a 12 volt battery:

201 * 5 + 226 = 1231g

20 AH * 12 V = 240 W-H

240 WH / 1.231 Kg = 195 WH/Kg

Again this is for the electrodes themselves. The case and electrolyte

will reduce this figure. However, it is perhaps instructive to note

that current lithium batteries are said to produce around 80 to 120

WH/Kg (there may be some somewhat better), and

that by adding less inert and heavy conductive metal filler powders,

lower current

but higher energy per weight Ni-Mn can be achieved.

Testing the

Battery

When the Battery was assembled, I tried charging it...

with

the usual disappointing results.

At least a couple of times I almost gave up. But

this time, fixing obvious problems that soon arose, trying a few things

and, mostly, sheer persistence

paid off, because in fact it took weeks for it to come up to its

expected voltage

and stay there when the charge was removed. Later I learned of a faster

way of 'formation' of the electrodes to get the initial charge.

First I decided to fill it with

electrolyte, a flooded cell instead of a dry cell. It worked way

better. I could put in hundreds of milliamps of charging current

instead of tens, and yet the voltage stayed much lower. I decided it

would have to be a flooded cell instead of a dry cell. (Later I

reconsidered this.)

Also the pressure crept up visibly to 5 PSI as I watched

for a few minutes.

In 2-1/2 hours it was up to 18 PSI. Through the clear plastic lid I

could see the water bubbling. I unscrewed the pressure gauge to release

the pressure. I decided it would also

have to be a vented cell. Anyway my sealed case design seems

vindicated! With a glued-on bottom, a rubber gasket at the top, and the

bolts done up, there was no sign of leaks.

There was quite a lot of bubbling for the first day, which

didn't smell like hydrogen AFAICT. This subsided, but after about a day

the currents also

dropped a lot and the charge voltage went way up, to over 3 volts. It

turned out to be

because the copper connections

of the positrode had corroded entirely away - and a piece of the

stainless steel

terminal bolt in contact with the copper was eaten away. It looks like

copper is good for the negatrode, but not on the plus side, and also

that stainless steel wasn't going to work either.

Corroded bits of copper mesh and wire from the nickel positrode.

The positrode was pieced back together, on a sheet of nickel-brass

with

a

stainless steel screen.

This was wrapped in cellophane and re-used.

So the question is what to use for connections? I

suspected the nickel-brass (AKA "German silver", "nickel-silver")

wouldn't

last either, but I stuck a sliver of it in behind the now unconnected

electrode to try it out. The battery went back to accepting high

currents without the voltage running away. I suspected that

only pure nickel was going to work for long, just like in alkaline

cells - if it worked.

Later I went down to Custom Plating and found they'd

nickel plate a good size chunk of my extruded copper mesh and a piece

of heavy nickel-brass wire for about $70. That should work except it

may corrode in from the cut ends eventually, and anywhere it gets

scratched during handling or when compacting the electrode. (Maybe

they'd plate finished assemblies for a reasonable price, too.)

Next I suspected there was a short circuit through the

separator

sheets (the Arches 90# watercolour paper and the cellophane). I took

the battery apart. I found 3 holes in the paper. I probably made the

holes sticking in the sharp sliver of sheet metal.

The negatrode

appeared to be in

fine condition. The positrode

fell apart, its copper mesh skeleton

dissolved away.

I reassembled the pieces on a sheet of nickel-brass, wrapped it in

cellophane, cut a new paper sheet, and re-assembled the battery.

Then I tested the pH. The pH was 12 or 13!

Evidently in spite of adding neutral KCl salt, I had

created an alkaline battery. That would explain the corrosion.

In retrospect it

doesn't seem too surprising, since the manganese (MnOOH - ?) gives off

OH-'es as it

charges, which will mingle with the K+'es in solution to form KOH. And

the Ni(OH)2 in the negatrode as well gives up its OH-'es one-time,

afterwards being fine metallic Ni. (I wonder what

happens to the Cl-'es? Probably they remain active in the solution,

especially seeing it isn't pH 14.) Here we see a situation analogous to

the lead battery renewal process, where starting with neutral sodium

sulfate salt in distilled water, the liberation of more sulfate from

the battery plates yields an acid electrolyte of sulfuric acid and

sodium bisulfate.

Evidently then nickel or nickel plated metal will be

required for the "+" side. I wonder how practical it is to make up my

own nickel plating solution, seeing that nickel mesh and wire seem,

absurdly, to

be 400 $/pound and up from anywhere I can find them?

This also means that the alkaline voltages from the table

should apply: +.48 or +.51 for the nickel (depending where you read it)

and -1.55 or -1.56 for the manganese, about

2.03 to 2.07 volts. Still much higher than Ni-Fe, -Cd, -MH or even -Zn!

After a few days the cell still didn't seem to want to

charge

further and come up to its proper voltage, like most of my batteries. I

decided to take it apart, rinse it out, and replace the grungy looking

electrolyte.

The manganese negatrode looked much the same as when I

made it and only a little colour was evident in the rinse bath. But as

I was rinsing it, I realized I hadn't heated it to cook the bit of egg

white that was in it. Could it have washed out or degraded, and that be

the reason it wasn't charging? If I couldn't make this battery work,

only a new negatrode would tell for sure.

The nickel hydroxide positrode, wrapped in cellophane,

oozed greenish and yellowish stuff from start to finish. What was all

that? Answering that question might also answer why the battery wasn't

performing as expected - after all, I know I had a working nickel

positrode earlier, that I had coupled with a commercial battery

cadmium negative.

Next thing to check in the replaced KCl electrolyte was the pH. After a

bit of time and charging, it was about 12, still very alkaline.

The negatrode was bubbling strongly under charge, even

worse than initially. The obvious suspect was the uncooked egg white.

A simple thing to try before making a new negatrode

suggested itself: dry the electrode, mix some egg white with water,

pour it on and let it soak in, then heat the electrode at about

110ºc in the oven for a while to cook it. I did this. Then

I

reassembled the battery cell and put in on charge. Soon it was up to

2-1/2 volts, and something like a white merangue formed above the

negatrode, which continued to bubble. It was yellow in places, where it

looked a bit like what was

leaking out of the positrode when I was rinsing it.

It still wasn't holding much more charge. I added a couple

of drops of methyl-ethyl keytone to the electrolyte. I don't know if it

helped. A day later, it was holding just slightly more charge.

The cell was, over the weeks, increasing in voltage. On

the 17th, I read a piece on "forming" iron electrodes in a flooded tank

with nickel metal "counter-electrodes" on both sides (doubtless

bubbling oxygen when charging the negatrode), even though the

electrodes were for use in a dry cell. That's probably the way it's

supposed to be done, and the way I should be doing the manganese ones.

Hydrogen

Overvoltage & Manganese

I should perhaps clarify in detail the reason for the

antimony and

the egg white. A small amount of a transition metal in the

negatrode raises its hydrogen overvoltage and this has been helpful

with zinc, although zinc does charge without it under normal

conditions. The transition element

may be added as its oxide or in pure

metal form.

Antimony looks like

the best to me and is evidently

non-toxic, and the oxide is cheap at pottery supplies. Furthermore,

there are indications that antimony (specifically) might cause a

catalytic reaction to recombine hydrogen and oxygen into water,

reducing gas pressure inside the battery. This has also been done using

cerium and platinum, but platinum is costly.

The manganese metal/hydroxide reaction is 300mV higher

voltage than zinc,

which has previously been considered to be the highest energy negatrode

substance usable in aqueous solution. Instead of the manganese

charging, hydrogen bubbles off the electrode: the water charges first.

What I've never seen mentioned in battery literature is this (Science

Magazine (23 October 1964, article: Effect

of Traces of Large Molecules

Containing Nitrogen on Hydrogen Overvoltage):

"Organic amines, present in very small

concentrations (below 10-6

M) in 0.1

N H2SO4,

cause a significant increase in hydrogen overvoltage, the

effect being stronger the higher the molecular weight. The

increase could be accounted for by the usual site-blockage concept.

In the case of egg albumin, a drastic increase of over 300

mv was observed at 12.5 ma/cm2 for a concentration of only

0.01 part per million. A new mechanism is proposed in which the

dielectric constant and hydrogen-ion activity are believed to

be depressed in a region twice as thick as the usual transition region."

Note that the "drastic increase of over 300 mV" is the

very voltage

by which manganese exceeds zinc in alkaline solution, and zinc charges.

And that increase was

given for

an acidic solution and a very small concentration of albumin. It is

probably even higher in alkaline solution, perhaps 0.5 volts or more,

and with a greater concentration. Although the hydrogen overvoltage is

different for different electrode metals, the antimony plus the egg

albumin should surely provide enough increase to enable manganese to

charge. Enabling manganese high voltage negatives in batteries using

the 46 year old albumin finding is a fine new piece of "open

technology"!

(BTW the reason

I don't use zinc is because of its problem of

migrating, and growing "tentacles" (dendrites) during cycling, via the

temporarily dissolved zincate ion. The migration of zinc to the

positive electrode gradually reduces the capacity, and often the

tentacles short

out the battery. Otherwise Ni-Zn would make great higher energy

batteries! Cadmium, right under zinc in the periodic table, has the

same problem and Ni-Cd batteries rarely last their nominal rated 200

charges.)

Reducing

Manganese Dioxide

I added plenty of H2O2 to 10.00 grams of MnO2, to try to

determine what form it became by the weight of the product. There was

lots of bubbling. Then it had to dry out. I

poured some water/H2O2 off once it settled.

MnO2 [IV] - molecular weight 87 - 10.00 g

As I saw it, the chief possibilities and their weights were:

MnO [II] - 71 - 8.16 g

Mn2O3 [III] - 9.08 g

MnOOH [III] - 88 - 10.11 g

Mn(OH)2 [II] - 89 - 10.23 g

The measured weight once it had dried was 10.05 grams.

(The resolution of the scale is only .05g.) I think it

lost a tiny amount of Mn material in the water I poured out. I think

I'll assume it's MnOOH. That's closest by weight

and a likely reaction result. The best result would have been valence

two - MnO

or Mn(OH)2. A less likely possibility is that it acted simply as

a catalyst that caused the H2O2 to decompose and is still MnO2.

Whether it's MnOOH, Mn(OH)2 or MnO2 it's about the same

weight to attain the same amount of manganese. Only the balance of

charge shifts. This can be compensated initially by the proportion of

Mn powder added, or later by charging or discharging the

nickel side - if I recognize that it's out of balance.

Note: On the 17th I found a means of independently

charging/forming the negatrode, which means it could perhaps be brought

to the desired state of charge independently of the positrode before

the battery is assembled.

Useful

Miscellaneous Notes/Conclusions

Clear Plastic Covers

I found an advantage to having a clear bottom on the

battery: most of my covers have leaked under pressure. With the clear

bottom, I can

see how well the glue is covering and if there are air bubbles or gaps.

I can also see that the glue seal is much better if the whole thing is

well clamped while it's wet (not a surprise!), which I did by

assembling the case and

screwing the top cover on.

I can see that for a production situation, it would be

much the best to make molded cases with only the top to be fitted

afterwards -- as is the case with most liquid filled batteries. Pockets

molded in to put in screws to hold the top on would be superior to a

glued-on top IMHO. Then defective batteries could be repaired. Of

course, I'm still thinking of small production. If virtually every

battery comes off the line perfect and lasts for 10 or more years in EV

use, it would matter little.

But it looks like it's all academic... Ni-Mn cases will

need to be vented and flooded rather than sealed and dry cells.

Vented Flooded Cell Cases and Battery Sizes

After trying the battery and seeing that they were going

to have to be vented flooded cells, suddenly the whole case problem

becomes much easier - it doesn't have to hold pressure.

Making the cases from flat pieces of plastic and gluing

them together (well clamped till the glue sets!) as I had tried earlier

on is probably simplest the way to go. If I or anyone gets the chelated

lanthanum perchlorate chemistry going for higher energy density and

lower pressures, dry

cells in sealed cases will likely again become a topic of interest.

And the terminals

don't have to go

through and hold against pressure without leaking. Indeed, for homemade

batteries I see no reason not to just stick the collector wires through

tight holes in the lids, or maybe loose holes and use RTV rubber cement

or silicone to

make a seal. It solves how to connect internal terminals in a way that

won't corrode - by eliminating those connections entirely.

A second aspect of vented cases is the elimination of size

constraints. Where I would have used about 3.25" x 2.5" x 6.5"

(internal) size for a 12 volt, 30 amp-hour battery that would take the

pressure, I could now go for any size, even as big as typical lead-acid

batteries, but with very high amp-hours. The one constraint is the size

of individual electrodes, which still have to be strongly compacted.

One thought would be to make a battery of the same 3" x 6"