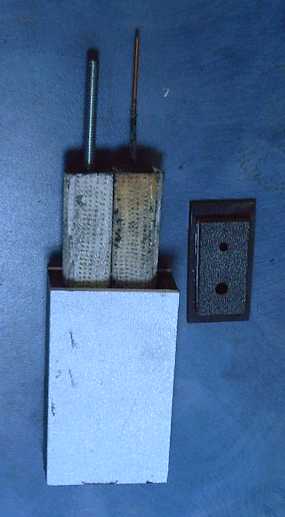

Once I had the overvoltage problem figured out, manganese

for negatrodes at long last worked fine.

Once I had the overvoltage problem figured out, manganese

for negatrodes at long last worked fine.  After four

years of mixed results at best, a battery with

all the features above worked well the day before my battery making

talk at Ideawave 2012. A Times-Colonist newspaper reporter interviewed

me, and I wrote him a brief description of the battery, leaving out

most of the ad nauseum technical details I always so scrupulously put

in. It probably bears reprinting here (re-edited):

After four

years of mixed results at best, a battery with

all the features above worked well the day before my battery making

talk at Ideawave 2012. A Times-Colonist newspaper reporter interviewed

me, and I wrote him a brief description of the battery, leaving out

most of the ad nauseum technical details I always so scrupulously put

in. It probably bears reprinting here (re-edited):

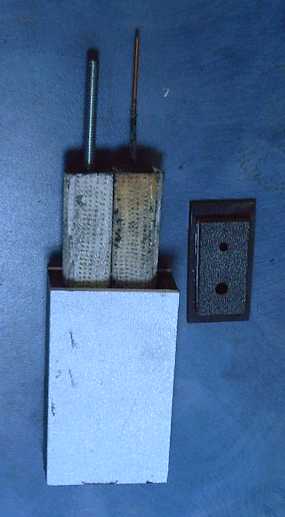

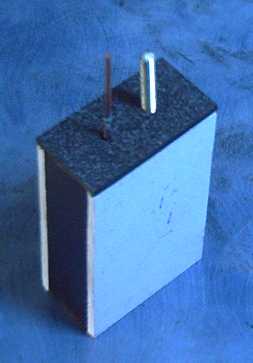

* Take a piece of fat

polyolefin heatshrink tubing [electronics parts

store] and put lots of tiny

holes in it (sewing machine with no thread)

* Take a piece of fat

polyolefin heatshrink tubing [electronics parts

store] and put lots of tiny

holes in it (sewing machine with no thread) Zinc should

work without overvoltage raising... but better with it than without.

First I crunched up some stibnite with a hammer on an anvil to make it

as fine as possible, as I had noticed even the 'fine' powder did a lot

of crunching when ground with mortar and pestle - it's too coarse.

Veegum for glue. About

6 grams stuffed into the 'pouch', theoretically about 3-1/2 amp-hours

worth. The nickel electrodes should be of similar capacity.

Zinc should

work without overvoltage raising... but better with it than without.

First I crunched up some stibnite with a hammer on an anvil to make it

as fine as possible, as I had noticed even the 'fine' powder did a lot

of crunching when ground with mortar and pestle - it's too coarse.

Veegum for glue. About

6 grams stuffed into the 'pouch', theoretically about 3-1/2 amp-hours

worth. The nickel electrodes should be of similar capacity.

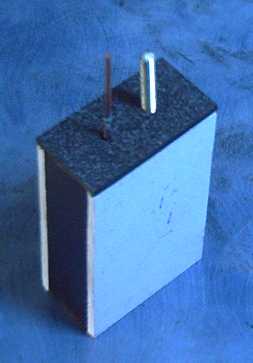

The remaining

question then was whether it would be

practical to punch the multitude of tiny holes - preferably in the flat

sheet before forming it into a tube - assuming they wouldn't close up

when heated. If that could be done, it looked like I could soon have

real, working electrodes... followed by real, working batteries. Better

chemistry was merely a bonus!

The remaining

question then was whether it would be

practical to punch the multitude of tiny holes - preferably in the flat

sheet before forming it into a tube - assuming they wouldn't close up

when heated. If that could be done, it looked like I could soon have

real, working electrodes... followed by real, working batteries. Better

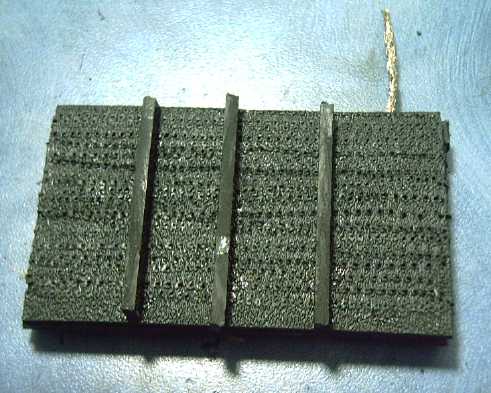

chemistry was merely a bonus! After thinking about a few ideas, I started to realize that 1/2" square

is probably just too fat. It's 6mm from the wire to the corners, where

other alkaline electrodes are 1mm or less from any point to a current

collector. 1/4" square electrodes would have four electrodes where one

1/2" one is. And they would be only 3mm to the corners (2mm with a fat

center conductor), and there'd be 4 wires in place of one. That's a

pretty small size to fill by hand, but undoubtedly more in line with

the electrochemical requirements. The big challenge then is to find

ways and means to make it very fast and easy to make each individual

small electrode. (How do those cigarette roller/stuffer things work?)

After thinking about a few ideas, I started to realize that 1/2" square

is probably just too fat. It's 6mm from the wire to the corners, where

other alkaline electrodes are 1mm or less from any point to a current

collector. 1/4" square electrodes would have four electrodes where one

1/2" one is. And they would be only 3mm to the corners (2mm with a fat

center conductor), and there'd be 4 wires in place of one. That's a

pretty small size to fill by hand, but undoubtedly more in line with

the electrochemical requirements. The big challenge then is to find

ways and means to make it very fast and easy to make each individual

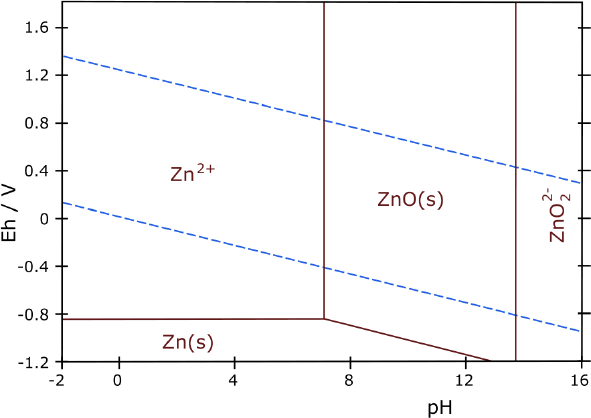

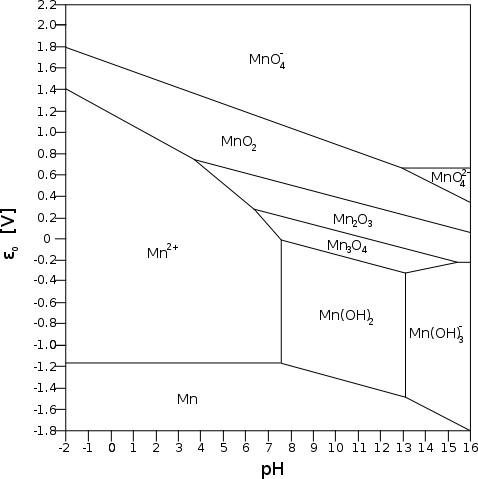

small electrode. (How do those cigarette roller/stuffer things work?) Referring to the Mn Pourbaix diagram, it appears that the manganate ion

will only form at pH 13 or above, but at about +.65 volts, which is 30%

higher energy than the .5 volts of the NiOOH reaction on top of the

higher amp-hours, and probably higher maximum amps capacity owing to

lower internal resistance with the manganate spinel structure.

Referring to the Mn Pourbaix diagram, it appears that the manganate ion

will only form at pH 13 or above, but at about +.65 volts, which is 30%

higher energy than the .5 volts of the NiOOH reaction on top of the

higher amp-hours, and probably higher maximum amps capacity owing to

lower internal resistance with the manganate spinel structure. On

consideration, this or something akin seems more

likely. The

main differences then would be the high conductivity of nickel

manganate

compared to nickel hydroxide, allowing higher current flow, and that

nickel manganate and the charged coumpounds are (seem to be) insoluble

at neutral pH where the reaction voltage is around +.95, rather than

the usual +.5 in alkali.

On

consideration, this or something akin seems more

likely. The

main differences then would be the high conductivity of nickel

manganate

compared to nickel hydroxide, allowing higher current flow, and that

nickel manganate and the charged coumpounds are (seem to be) insoluble

at neutral pH where the reaction voltage is around +.95, rather than

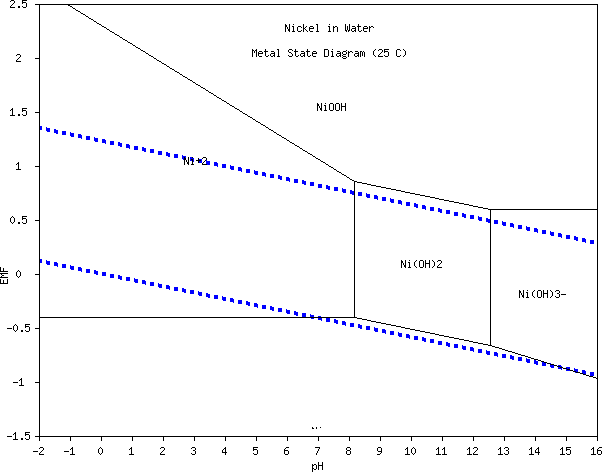

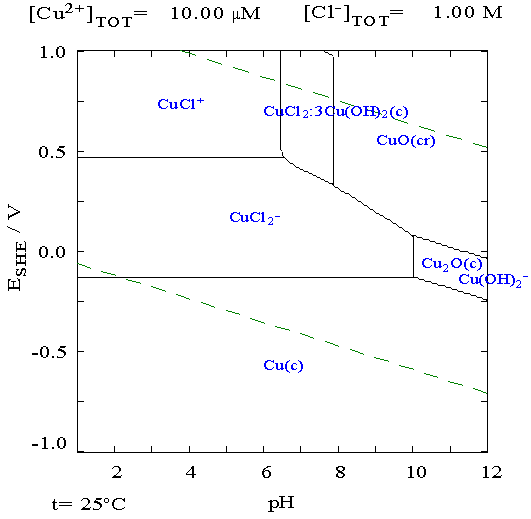

the usual +.5 in alkali. It occurred to me

that altho I had no 'standard

hydrogen electrode' with which to determine individual electrode

voltages, I could stick a copper wire into the liquid. With the pH and

a copper Pourbaix diagram, I could find the electrode voltage of copper

metal, and subtract that from a measured voltage to get the voltage of

individual electrodes. It appeared that in chloride solution (there

were four separate Pourbaix diagrams for copper in different solutions)

it should be -.13 volts from acidic pH up to about 10, but the readings

didn't jibe with approximately known figures. Maybe I should try zinc.

It occurred to me

that altho I had no 'standard

hydrogen electrode' with which to determine individual electrode

voltages, I could stick a copper wire into the liquid. With the pH and

a copper Pourbaix diagram, I could find the electrode voltage of copper

metal, and subtract that from a measured voltage to get the voltage of

individual electrodes. It appeared that in chloride solution (there

were four separate Pourbaix diagrams for copper in different solutions)

it should be -.13 volts from acidic pH up to about 10, but the readings

didn't jibe with approximately known figures. Maybe I should try zinc.