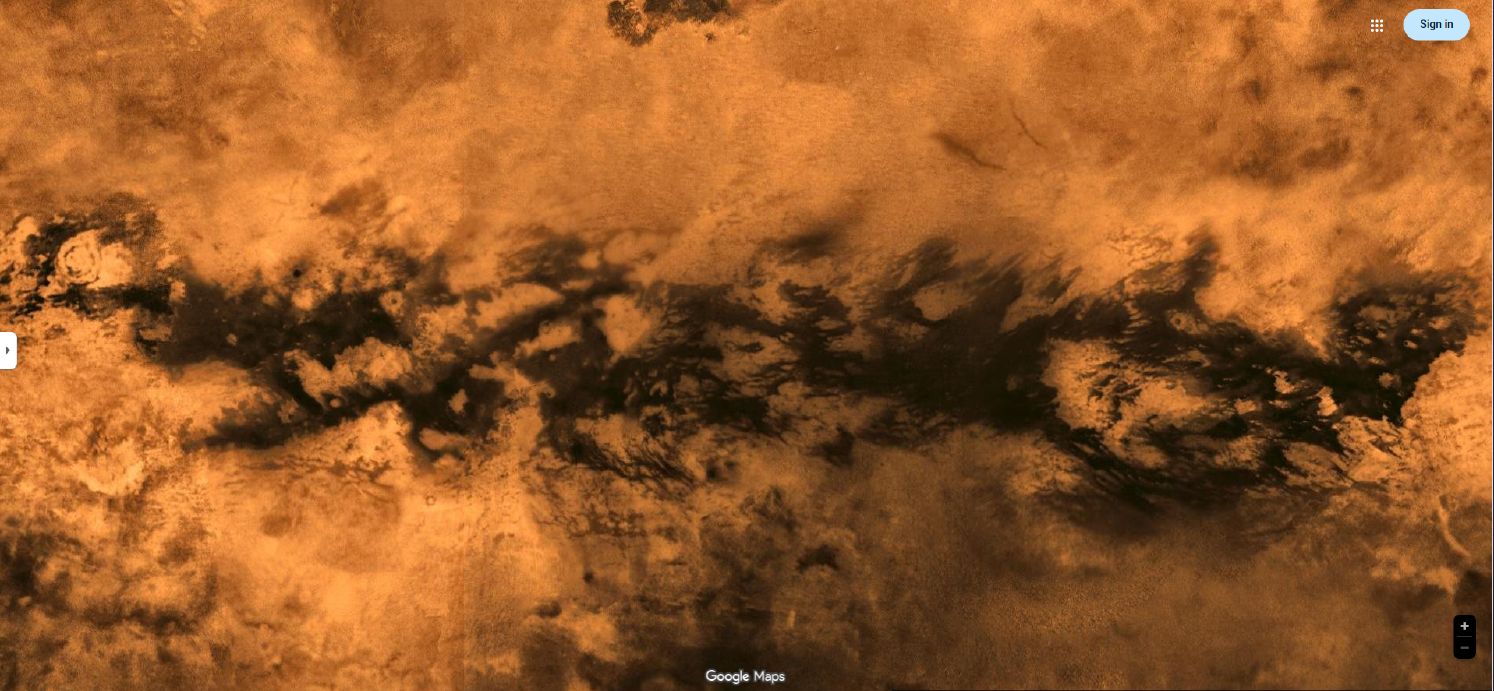

The shallow, duney, flowing seas of Titan's equator and tropics.

The drifting sediments reveal the generally stronger eastward flows.

(reduced image)

https://google.com/maps/space/titan/@7.9975347,68.0273437,14129815m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDkyOS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D